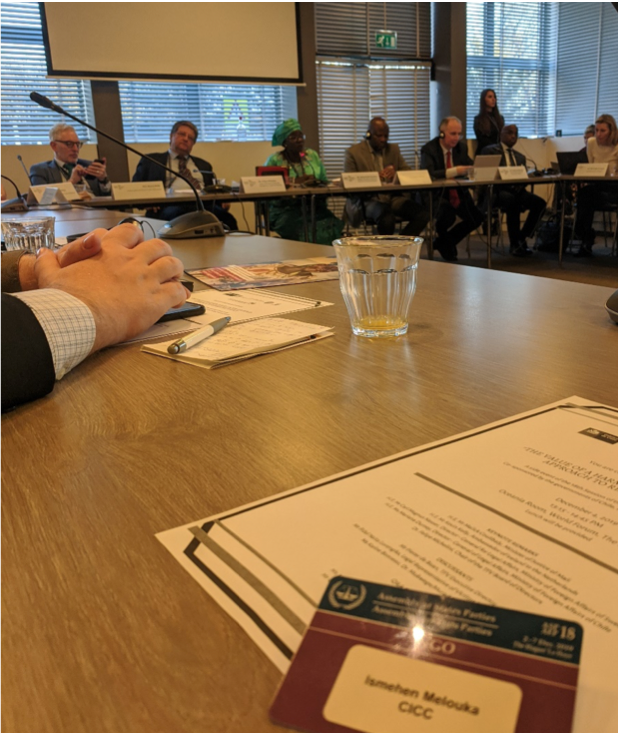

On the third day of the 18th annual session of the Assembly of States Parties (ASP) to the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) hosted a side-event titled “The value of a harm-based, victim centered approach to reparative justice.” Co-sponsored by the governments of Chile, Finland, Ireland, Mali and Sweden, this event featured panelists Mr Pieter de Baan, President of the TFV; Ms Karine Bonneau from the Global Survivors Fund; and Mr Fidel Nsita, Legal representative of victims in the Katanga and Al-Hassan cases. Several speakers were also invited, including Mr Malick Coulibaly, the Minister of Justice of Mali, Mr Kevin Kelly, Ambassador of Ireland to the Netherlands, Ms Mariana Durney from the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Dr Felipe Michelini, Chair member of the TFV Board of Directors.

On the third day of the 18th annual session of the Assembly of States Parties (ASP) to the International Criminal Court (ICC), the Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) hosted a side-event titled “The value of a harm-based, victim centered approach to reparative justice.” Co-sponsored by the governments of Chile, Finland, Ireland, Mali and Sweden, this event featured panelists Mr Pieter de Baan, President of the TFV; Ms Karine Bonneau from the Global Survivors Fund; and Mr Fidel Nsita, Legal representative of victims in the Katanga and Al-Hassan cases. Several speakers were also invited, including Mr Malick Coulibaly, the Minister of Justice of Mali, Mr Kevin Kelly, Ambassador of Ireland to the Netherlands, Ms Mariana Durney from the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Dr Felipe Michelini, Chair member of the TFV Board of Directors.

During this session, participants discussed the importance of a harm-based, victim centered approach to restorative justice within the ICC framework. Restorative justice, also known as reparative justice, is defined as “an approach to justice that focuses on addressing the harm caused by crime while holding the offender responsible for their actions, by providing an opportunity for the parties directly affected by the crime – victims, offenders and communities – to identify and address their needs in the aftermath of a crime.” As stressed by panelists at the side-event, restorative justice is in fact the only way for an institution like the ICC to fulfill its mission to end impunity while preventing further crimes.

The Trust Fund for Victims

According to the various panelists, the TFV is an effective tool for the Court to provide justice to victims of international crimes. It is a unique international justice mechanism which carries a double mandate: to provide reparations to, and to assist the victims of the most heinous international crimes committed (see articles 75 and 79 of the Rome Statute and Rule 98 of the Rules of Procedure and Evidence). The TFV notably implements the reparation orders of the Court against the convicted. Various forms of reparations are provided for in the Statute, including rehabilitation, compensation, and restitution (Article 75).

Whereas reparations may only be ordered after an accused is convicted by the ICC, the TFV’s assistance mandate enables it to provide support to victims at all stages of the judicial process. This assistance can take several forms, including psychological and physical rehabilitation, as well as material support. Additionally, as both victims and their families are eligible for assistance, the support provided can reach much more individuals both directly and indirectly impacted by international crimes. The TFV’s assistance mandate thus helps filling the gap between victims of specific situations covered by reparations orders from the Court, and those who will never see their case proceed to trial. As the Court has concluded three trials resulting in reparation orders for victims, namely the Katanga, Lubanga and Al Mahdi cases, the TFV has had opportunities to fulfill its reparation mandate.

Meeting victims’ needs and expectations

One of the issues raised during the side-event pertained to victims’ expectations regarding reparations. From the perspective of Fidel Nsita Luvengika, survivors tend to overestimate the capacity of the Court, especially when it comes to reparations. As the accused are often found destitute, the Court invites the TFV to deploy its resources to provide reparations to victims, as in the Katanga case. In this case, the reparation order included both individual and collective reparations. Due to the large number of victims (more than two hundred), a symbolic monetary compensation of 250 US dollars was awarded to each individual victim. In addition, as a collective reparation, the construction of new infrastructures was ordered, including schools and hospitals.

However, a lot of victims in the Katanga case expressed doubts as to the relevance and legitimacy of collective reparations. According to Mr. Luvengika, although some victims did value collective reparation, others felt like the Court did not acknowledge their individual stories when ordering these measures. He told the story of a woman who had lost everything, including her assets and home, and who felt that the collective reparation ordered, namely the construction of a new hospital in her area, was of limited relevance as it did not meet her needs and did not allow her to heal. Further, Mr. Luvengika noted that some victims were disappointed with their experience of the ICC judicial process and felt that their views and concerns had been largely ignored.

“A justice given without even listening to the victims’ voices is a justice that misses the main principle of reparation.” – Mr. Fidel Nsita Luvengika, Victims’ Legal Representative in the Katanga and Al-Hassan cases

A victim centered approach

At the side-event, all participants emphasised that justice cannot be achieved without considering the victims’ reparation needs. One of the ways for ensuring that these needs are heard, understood and met consists in adopting a victim centred approach throughout the judicial process. Such an approach allows for restorative justice to be performed, thus allowing victims to gain a greater sense of dignity while preventing further victimization.

“Restitution is felt inside the body… Today I feel like a man again, it restored my dignity… Before forgiving, the convict must first repair…” – Survivor and beneficiary of the TFV in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as quoted by Mr. Fidel Nsita Luvengika, Victims’ Legal Representative

Reparative justice has a place in international criminal law, just like the fight against impunity. These two objectives must be pursued together to foster peace and reconciliation in the affected communities.

Chair of the TFV Board of Directors Felipe Michelini stressed that for victims’ needs to be met within the ICC framework, it is crucial that all States Parties ensure the effectivity of the TFV by actively collaborating with it. In addition to contributing financially, they must institutionalize victim reparations in their national laws, as well as raising awareness in the general population and the private sector. Also, while promoting accountability, States should bear in mind the importance of reparations for achieving reconciliation in war-torn countries.

To conclude, the importance of funding and supporting the TFV cannot be overemphasized, both for the victims and for the sustainability of the Court in the pursuit of its mandate. To achieve its fundamental role, the TFV needs the cooperation of all States Parties, non-government organizations, and the Court. Reparation can help restore peace within fragilized societies, thus realizing one of the objectives sought by both the Court and States Parties in fighting impunity.

This blogpost and the author’s attendance to the 18th Assembly of States Parties to the International Criminal Court are supported by the Canadian Partnership for International Justice and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Les réflexions contenues dans ce billet n’appartiennent qu’à leur(s) auteur(s) et ne peuvent entraîner ni la responsabilité de la Clinique de droit international pénal et humanitaire, de la Chaire de recherche du Canada sur la justice internationale pénale et les droits fondamentaux, de la Faculté de droit de l’Université Laval, de l’Université Laval ou de leur personnel respectif, ni des personnes qui ont révisé et édité ces billets, qui ne constituent pas des avis ou conseils juridiques.